Home

Artist's Statement

Recent Work

Older Work

Recognition

C.V.

Contact

Long Island Burning Bush (1989).

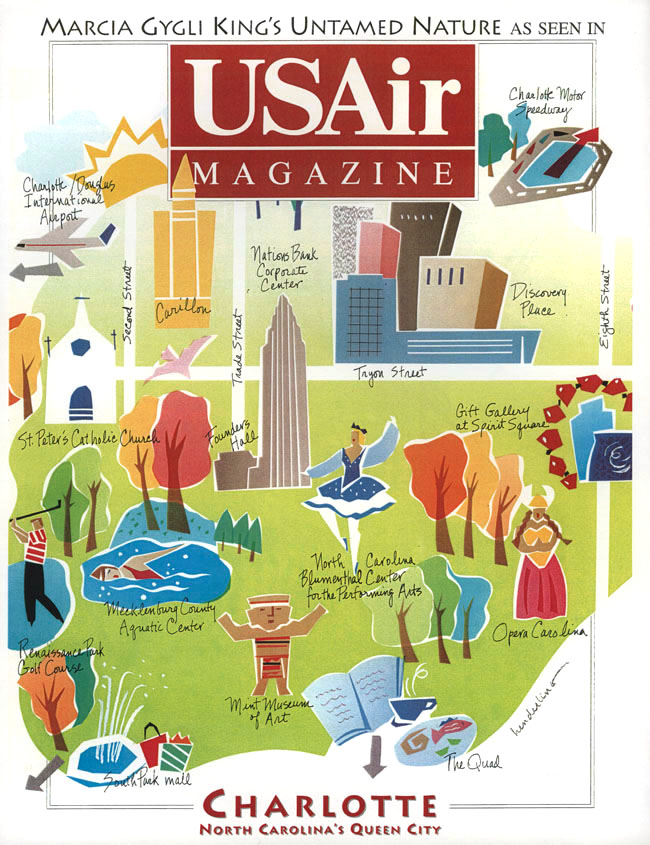

UNTAMED NATURE

By NANCY A. RUHLING

WITH A SWIRL OF COLOR, ARTIST

MARCIA GYGLI KING'S MASSIVE

LANDSCAPES AND SEASCAPES SHOW

THE STORM BEFORE THE CALM.

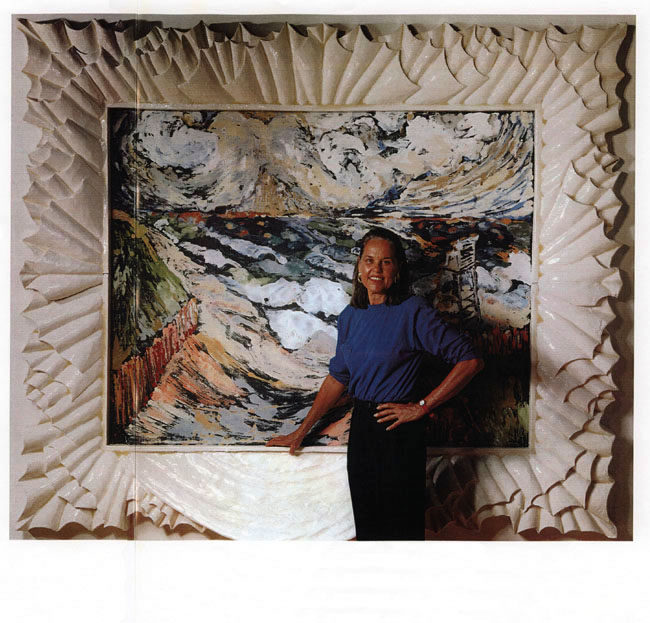

THE INTERIOR LANDSCAPE OF MARCIA GYGLI KING'S SoHo studio is stark white as far as the eye can see. The vast Manhattan loft has white walls. White ceilings. White drapes. White chair. White sofa. White lamps with white bulbs hidden by white shades. White clock. White vase.

King, it seems, saves all the color for her canvas landscapes, mural-sized sculptural paintings that pulsate with preying pinks, pandemonium purples, raging reds, yowling yellows, goading greens, brawling blues, and yes, even some writhing whites. "My landscapes and seascapes are not soothing," says King as she moves a 6-foot painting, a riot of color, into the glaring white light of the skylight.

"They are powerhouses. I wanted to stand up. I wanted to put some juice, some passion. I wanted to make my paintings full of energy, vitality, full of life," she says. "But it wasn't that it wasn't without risk. The risk was to paint that passionately."

It is a risk that has brought high recognition. King's works, studies of nature untamed, sell for $10,000 and up and are in the collections of some of the nation's leading museums, including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City; the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C.; the Cleveland Museum of Art; and the Arkansas Arts Center in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Under King's bold and brazen brush strokes, ocean waves cascade and roll, storms brew and spew spatters of kaleidoscopic color, and even innocent-looking gardens leap to life, pushing right out of the canvas and into the surrounding frame.

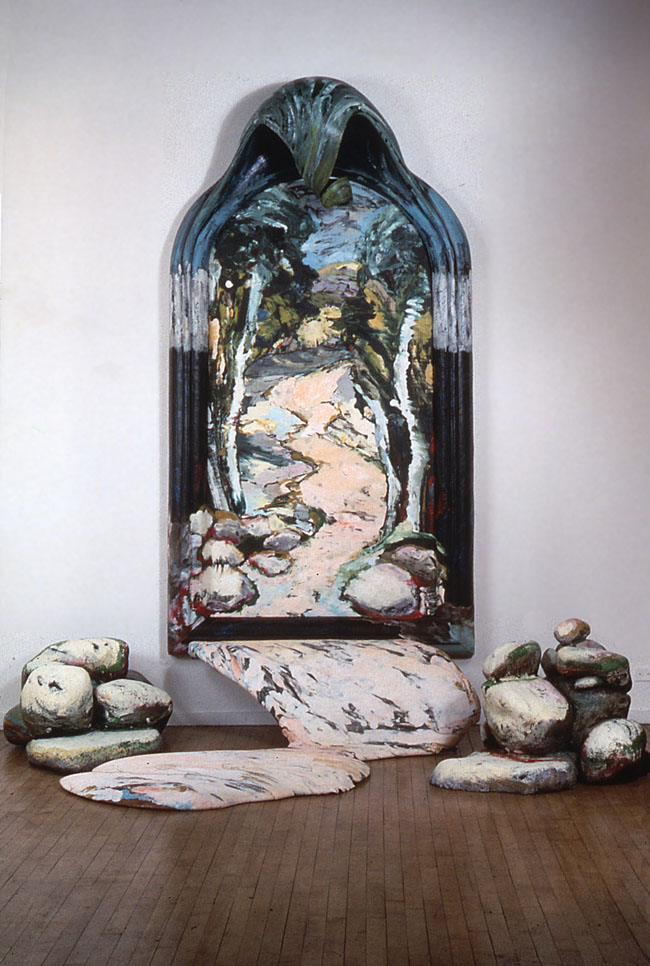

Springs Upstate (1990-1992)

This exuberance, this wondrous power of nature, both beautiful and awesome, is echoed in King's studio, where a human-sized ficus all but swallows up the sofa and an exotic night-blooming cereus threatens to take over the table or even the room.

"I tried to be delicate," says King, frowning, as if this word 'delicate" is not part of any language, much less her art, "but I found I was much more comfortable if I paint something that winds up and hits you."

The Nichols Barn - Sagaponak, Long Island

(1991-1992).

KING, A TRANSPLANTED SAN ANTONIAN WHO HAS lived in New York City for the past 15 years, decided to go for the one-two punch and make her works Texas tall because "a male art critic told me that if you want to make it in the art world, you have to paint big."

But it's not just her paintings that are big, it's her ideas. King deliberately infuses a bit of theatricality into her works "to get people to open up." Take Springs Upstate, for example, a 9foot-high stage-set-like arch from which "water" flows onto the floor and forms pools around a series of sculpted rocks. The image is evocative not only of the colossal paintings of the Hudson River school but of the pantheistic ecclesiastical art-glass windows of Louis Comfort Tiffany. But King tosses such loftiness to the wind with puckish humor. Atop the arch sprouts a grassgreen curlicue, a Shirley Temple lock.

When Springs Upstate was exhibited at New York City's Hal Katzen Gallery in 1992, King had a stroke of genius. She painted the spring so that it flowed out the front door of the gallery, down the steps, along the sidewalk, and into the sewer.

Spring on Interstate 90 (1989).

The public reaction was likened to a '60s happening. "People and dogs walked all over it all day," she says. "It was an environmental statement about how we are besmirching our water supply. People were going bonkers over it, they were even taking pictures of it."

King paints what she feels, and what she feels so vibrantly is found in nature, specifically scenes from upstate New York and from Long Island's Sagaponack, where she has a second studio in a barn. "I always go to the scene. When I'm in the Hamptons, I love to weed. It is the harmony of the earth, and I'm never more myself than when I'm walking on the beach."

Using oil sticks-"They are really great because they melt in the sun"-King sits on the beach and sketches. Then she begins what she calls "once-removed painting," or monopainting, in which she paints on acrylic plastic and presses a prepared canvas, which she has painted green, onto it so that the image transfers. She repeats this process a number of times, concentrating on specific areas, then works the paint with her hands, building up the color to create a dotted, dappled texture. Then she carves the frames, which continue the image of the painting, out of plastic foam and covers them with fibers and epoxy. Each work takes at least three months to complete.

Kendalia Herefords (1990-1992).

"There's always a lot of turmoil in any creative process," says King, who works on several paintings simultaneously. "A lot of these paintings have references to the past, but art can only come from what's inside of you. I love to have my work incubate because great things come to pass if you can let them alone and dream and think about them."

Although King began painting when she was a child, she took time to let her dreams and ideas about art incubate. She earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in English from Smith College, then a Master of Fine Arts degree from the University of Texas at San Antonio before heading for New York City.

RECENTLY, KING HAS BEGUN PAINTING PORTRAITS. "They are very different," she explains, "with a deliberate distortion of size." In one, a two-panel, 6-foot mural, a pair of eyes rimmed by red glasses is eclipsed by a people-sized pink and white lily. "If you knew my friend, you'd say this looks just like him," King says.

In another, a two-part portrait of King's 90-year-old mother, an elephantine white iris is balanced by a pair of ancient, arthritic hands that grope aimlessly for the life-giving sun.

The viewer feels the sweltering heat, the futility of the effort, the victory of nature over man, of death over life. The effect sets the nerves "all twanging away," King explains, which is just what she intends.

Marcia Gygli King and Storm Clearing (1989).

Nancy A. Ruhling is the home furnishings editor of Victorian Homes magazine.

Site created by Seale Studios