Home

Artist's Statement

Recent Work

Older Work

Recognition

C.V.

Contact

RELIEF PAINTINGS

1982-1984

by Eleanor Munro

The force with which a dominant theme can work its way to the surface of a visual artist's oeuvre, sometimes through many levels of camouflage and metaphor, is striking. To follow the theme's lead requires grace, courage, and an instinct for self-clarification on the artist's part. "I must crush self, to find Jesus," was the plaint of a nineteenth-century missionary woman whose letters I've read, who was subjected to other pressures. But we accept, instead, that to let that self emerge into full consciousness is fundamental to an artist's life. I was made aware of such a process underway in Marcia King's work when I went, not too long ago, into her Soho studio and saw there a standing lamp of normal appearance save that to it was attached, in defiance of lamp-logic and for no other purpose than what it, in the end, achieved, a triangular signal flag. Once I did what the flag commanded -stopped in my tracks and looked-I noted that the whole structure was covered with an odd sort of khaki polka dot. Both these formal elements-posture and pattern-bespoke a wish to speak out, even if the message, like the beat of an African talking drum, was in a language unknown to me. In fact, at the time, even the lamp didn't yet know the burden of meaning it was longing to unload.

The lamp was one of a series of objects King made earlier, when she was living in Texas and working in a mode one might call subterfuge. Others in the series were paper and cardboard structures, objects of impersonal experience like a swimming pool or a skyscraper. They too, however, were all plastered with the talking-dots, which served as what another writer correctly called a visual tease. That is, they started to tell a story, then turned mute and pretended to be just decoration. One of those works, however, almost came clean. It carried a signal-title, "Winged Sarcophagus." To someone on the right track, that title might have suggested what was in fact the dots' real source: Mexican Day of the Dead figures that Texans often pick up south of the border. Those folk-art figures are painted white and speckled with marks that represent disease and oncoming death. They are memento mori, full of resonances for a Hispanic Catholic third-world country. But the dialectic between health and decay is one of humanity's common experiences, and King, though approaching the theme obliquely, and for a while without full awareness, has not ever really deviated from it.

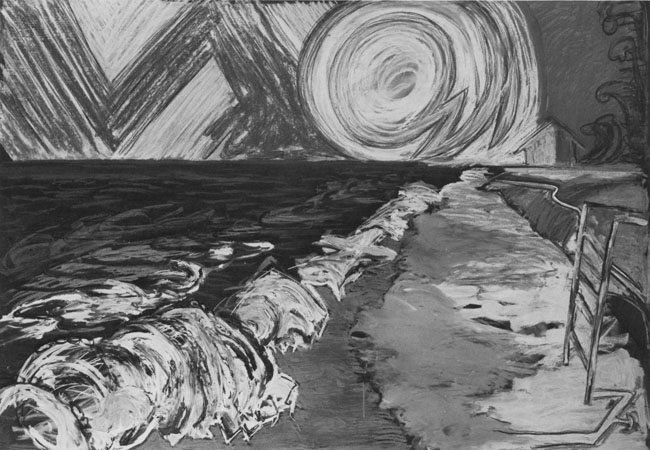

Southampton I, 1984. Acrylic, modeling paste, and pastel on paper. 62 x 72 in.

Her quilt Cantilever, for example (made for the 1983-86 traveling show The Artist and the Quilt), moved her in the direction of an imagery drawn more clearly from her own life experience. In designing it she found herself exploring visceral responses to human suffering in an abstract and cryptic way, in terms of cloth and thread. But King clearly wouldn't rest satisfied with a theme in wraps. It was the drive toward self-revelation on a deeper level of feeling and thought that, next in the order of her life, carried her forward to the stunningly authoritative series of paintings in this show that chronicle the death and transfiguration of a being of flesh and mind called Old Dog.

Old Dog was a magnificent Alsatian who guarded the King's family while her children grew and who accompanied her on her move away from the cardboard swimming pools to Soho. In among Manhattan's rooftops and sidewalks, then, King conducted her old friend down what a New Yorker supposes a Texan might call the Last Mile. "I knew her moods. I found the right pills for her pain. I walked her three times a day. If I kept her moving, she was OK. I knew it. Sure enough, I left her for two weeks with people who just let her lie around. I came back, and she was dead.

"But painting this old dog, I found once again I'd chosen the same subject."

The paintings-enormous, centered icons weighed down with chunks, gobs, and welters of applied material-have, each one, the force of revelation. If the lamp longed to speak but was silent, the painted dog speaks. The images record without the slightest ambiguity nuances of canine posture that, in turn, reflect states of feeling and degrees of awareness of fate that are quintessentially human. Taken seriatim, the scenes of the dog's slow walk toward destiny unfold with the momentum of a staged play.

But something else took place along the way. The very act of centering herself for a while on a loved animal as a metaphor for life and death dislodged from the artist's memory two vehement images, at once monumental and familial. They come to us as a pair of ancestor portraits, female and male, or rather both androgynous and tumescent with psychic energy. Each is swathed in Renaissance costume that glitters and bulges with protruding undervestments, as if neither subject could conceal the multiple layers of her or his being. Imperiously posed, they level not-quite grateful stares upon the artist who, with her brush and her hammer, delivered them out of whatever substates of her own awe, fear, and adoration they dwelt in before. Moreover, Cappie, the artist's mother, clutches to her breast a real satchel, in which, we imagine, is a queen's-nest of lists, maps, notes, pencils, and so forth that, in the transmutation of time and memory, will probably become a germinating-bed for her daughter's future work.

In fact, a further mutation in King's ongoing theme is discernible in the works in this exhibition, in just those agglomerations of impasto and stuck-on materials she put to simpler use before. In Dog with Bark, for instance, thick shadows lie heavily across the back, while a fluorescent tangle of lapis blue has piled up by the dog's ear. The visual trope for disease endures: while aging, this old dog grew deaf. Blue pigment, laid down in these snarls, signifies the condition, as the polka dots did earlier. But in other works in the series the sign has enlarged even more to become an amorphous burgeoning of material that might be named Gray, and that carries an implication of metaphysical meaning, beyond specific color or form. In Eternal Energy, for instance, which is the eschatological finale to the Old Dog series, the creature-object has evanesced, leaving behind but a ghostly mask, drained of personality, seen in the nightmare moment of being pushed off this green globe by riptides of the Gray.

Any element obsessively worked by King carries its charge of meaning. In Francis II, the Gray comes baled as oldfashioned columns topped with capitals like frozen waterspouts. In the Southampton Storm series, the bales have shattered to release free-floating wedges or wavelets, in which disoriented brushstrokes veer about. In Chili Queen, the Gray even folds back like a magician's handkerchief to expose, underneath, the old malignant dots.

The Grays are made of thick paint or of papier-mâché that "looks like cement," as King says, or else of Styrofoam cut, mashed, pounded, and glued to the canvas. Laboring to put into words what use this last material has for her, King gestures with both hands to show how she fights it. "It's intractable. It counteracts. It has tooth. It toughens. It won't be unctuous."

The Gray, then, surges up continually as antithesis to the "unctuous" and shapely drawing of images. Continually it has to be fought down. Surely it is to be feared and guarded against in one's life and also one's work, for one can see, in the Storm series, how it breaks out of the spume of disintegrating waves, collapsing on a beach. A turgidity, a glut of stuff extruded willy-nilly into space, King's Gray is a-human, morally neutral, and aesthetically void. It might be called brute power of expansion. Yet, and also therefore, this artist knows its worth and use, and names it "free energy"

Turning to art history, King likens the overload on some of her canvases to the profusion of mass and texture on the ceramic roundels of the della Robbia family, in which mothers and babies are tightly framed by thick wreaths and bunches of swollen fruit. The Old Masters, she concludes, worked that glut and contradiction as the water table or subsoil out of which their momentous sacred images came forth, projecting out beyond the wreaths like weighted blooms. The terms have changed, of course, but King's insight remains relevant. Her images, which now have the projective vehemence of thematic material raised to consciousness, do dominate, while feeding on for their very life, all that glut and contradiction, all the waste of death they have worked their way through. Such is the strange push-me-pull-me procedure of making art, and such is its triumphant end and, perhaps, even its evolutionary purpose. "I myself work from a whirling mass of things," says King. "Time and time again, I get out my bags of junk." She dives behind a door in her studio to drag out several bag-ladies' treasuries of old paper, cardboard, glitter, scraps of wood, dried chili peppers, twigs, cloth. "Sometimes I think to myself, I could just paint. But I look at the junk. And the junk triggers me. And suddenly I come alive."

To "come alive," then, is to oppose self to entropic junk and hold the line. Yet it is true that all the time, one remembers what one is really dealing with. A work with many resonances is Sunny Day on the Roof. Old Dog lies there, moored in King's fine architectonic draftsmanship. A little way off, three solid watertanks support, on black founda- tions, their heavy-pressured reservoirs. All tides are out, the empty rooftops say.

Then Old Dog raises her head. She cocks her signal-flag ears. In the distance, she hears the boom of the uncontained sea. We see that sound.

It rises, five jets of dark red Gray, from the deep streets below.

Sunny Day on the Roof, 1983. Pastel on paper. 26 x 40 in.

Site created by Seale Studios